The Museum’s collection of objects from the Islamic world is a broad and diverse spectrum of material culture stretching from West Africa to Southeast Asia. Made up of over 100,000 objects from the 7th century to the present day, the collection has grown over two and a half centuries through generous donations by individual collectors, curators and organisations, archaeological excavations, anthropological field research, and acquisitions. The collection represents an extensive array of material, including well-known masterpieces of Islamic art and the objects of the everyday, ranging from archaeology, coins, shadow puppets, traditional textiles and dress, to the arts of the book and contemporary art.

The first objects in the collection came from Sir Hans Sloane (1660–1753), a physician who amassed material from every culture (his entire collection amounted to around 71,000 objects), which he acquired to understand and tell the story of humankind. He bequeathed his collection to the nation following his death in 1753, and this formed the founding collection of the British Museum. His objects from the Islamic world include an important group of Persian amulets with Qur’anic inscriptions, which were translated for Sloane by Suleiman Diallo – a Muslim from Bundu (Senegal) brought to London in 1733 as a slave - and later freed.

Amulet with Arabic inscription, Iran, 1650-1700

Amulet with Arabic inscription, Iran, 1650-1700

It was under Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks (1826–1897), Keeper of British and Medieval Antiquities and Ethnography, in the 19th century, that the collection began to grow significantly. Franks is regarded as the Museum’s ‘second founder,’ adding over 3,000 objects from the Islamic world to the collection. He had a clear idea of what types of objects the Museum should collect, and focused particularly on objects that bore dates, makers’ names and inscriptions.

Safavid dish, Iran, AH 1109 (AD 1697-98)

Safavid dish, Iran, AH 1109 (AD 1697-98)

Among the friends of Franks were a group of major collectors who included Frederic Du Cane Godman (1834–1919) and John Henderson (1797–1878), whose collections also came to the Museum. Among the highlights of Henderson’s collection is an important group of ‘Veneto-Saracenic’ wares, metalwork made in Egypt for Italian patrons.

Mahmud al-Kurdi metal dish, Egypt or Syria, 1460-1500

Mahmud al-Kurdi metal dish, Egypt or Syria, 1460-1500

Godman’s unparalleled collection of Ottoman Turkish ‘Iznik’ pottery, lustre ‘Kashan’ wares from Iran and magnificent ‘Hispano-Moresque’ ceramics from Spain - some 600 pieces – came to the Museum following the death of Godman’s daughter Edith, in 1983.

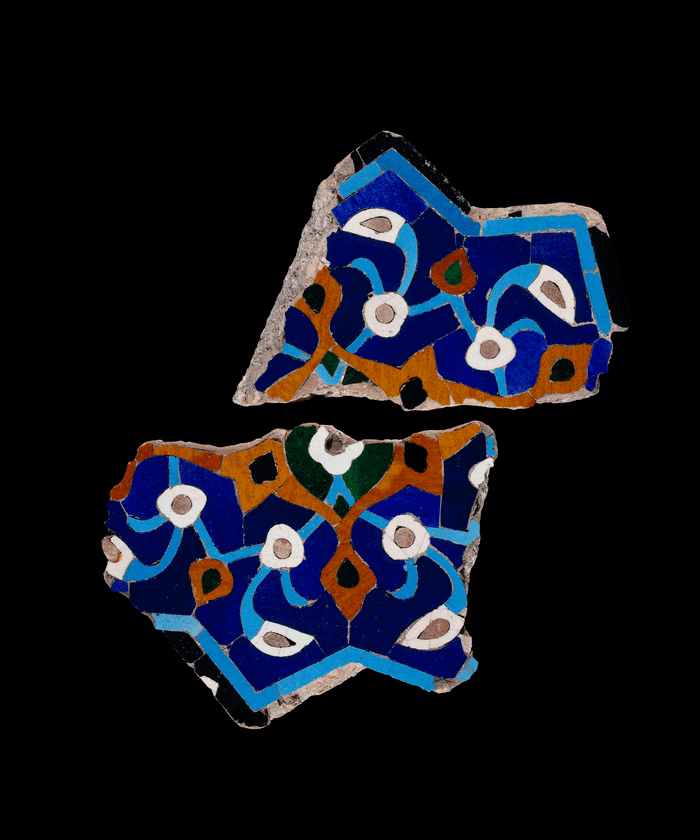

The 19th century was a period that marked Europe’s increased fascination with the Middle East. Bible tours to the Holy Land, as an extension of the Grand Tour taken by wealthy young European men and women, enticed more people to travel. Major discoveries were also being made at archaeological sites across the region. In the world of collecting, objects were being amassed in Europe, and international exhibitions, such as The Great Exhibition of 1851 at Crystal Palace, had a significant impact on the wider public’s taste for Islamic material culture: pottery, textiles, metalwork and other portable objects, fuelling a burgeoning market for such foreign ‘exotic’ wares. People did not even need to travel to the Middle East, as exhibitions and art dealers brought the Middle East to them. British officials, diplomats, soldiers, archaeologists, missionaries, linguists and others were also collecting objects in the regions in which they worked and travelled, which then found their way to the Museum. Sir Charles Edward Yate (1849–1940) for example, was a British soldier and administrator in India, who served in the Second Anglo-Afghan War (1879–80). In 1885, he witnessed the destruction of the minarets of the mosque of Gauharshad at Herat, in Afghanistan, and picked up some fragments of 15th century glazed tiles, which eventually reached the Museum.

Fragmentary 12-pointed star tile, Afghanistan, 1430s

Fragmentary 12-pointed star tile, Afghanistan, 1430s

The remarkable scholar Edward William Lane (d. 1876), whose publications include The Manners and Customs of the Modern Egyptians (1836), purchased while in Cairo, a Chinese porcelain flask full of water from the Well of Zamzam at Mecca.

Chinese porcelain Zamzam bottle, Egypt/China, 1750-1828

Chinese porcelain Zamzam bottle, Egypt/China, 1750-1828

In 1853, another celebrated figure, diplomat and traveller Richard Francis Burton (d. 1890) went on the Hajj pilgrimage to Mecca in disguise. His own simple metal Zamzam flask was donated to the Museum by his widow Isabel.

Archaeological finds form an important part of the collection. Two major sites in the Middle East have yielded a fascinating range of objects. From Samarra, in Iraq, the capital of the Abbasid caliphs between 836 and 892, carved and painted plaster that once lined the walls of houses and palaces, along with quantities of pottery and other objects, were excavated by German archaeologists Ernst Herzfeld and Friedrich Sarre between 1911 and 1913 and came to the Museum following the end of World War I (1914-1918).

Fragmentary wall-painting, Iraq, mid-800s

Fragmentary wall-painting, Iraq, mid-800s

Finds from the early medieval port site of Siraf on the Persian Gulf –excavated by David Whitehouse during the 1960s and 1970s - have revealed the role of this city in the story of the Indian Ocean trade when, as described in the tales of Sindbad in the Thousand and One Nights, the great ocean-going ships traded all around the Indian Ocean as far as China. Objects from all over the world have been found there, from Indian cooking pots to Chinese porcelain.

Handmade cooking pot, Iran, 600s-800s

Handmade cooking pot, Iran, 600s-800s

The Siraf finds also highlight the manufacture of objects of every day including jewellery made from mother of pearl shells.

From the time of its inception, ethnographic material - objects relating to the studies of peoples and cultures - was an essential component of the British Museum’s collection. A friend of Sir Augustus Wollaston Franks, Henry Christy (1810–1865), a wealthy businessman who was responsible for introducing Turkish towelling to Britain, bequeathed several thousand objects from the Islamic world to the Museum.

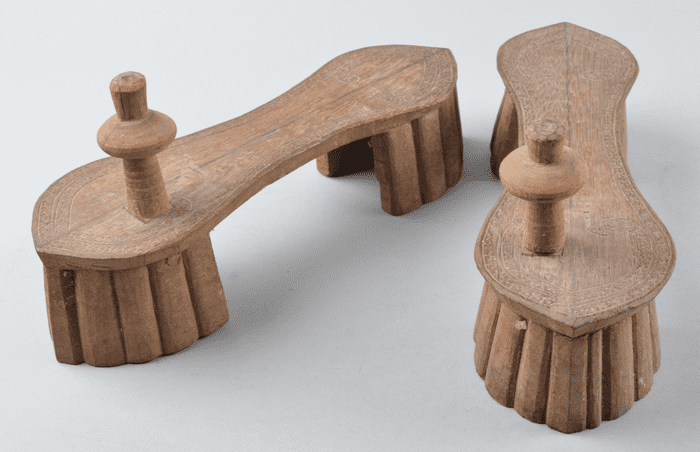

Bath clogs, Turkey or Syria, 1800-1900

Bath clogs, Turkey or Syria, 1800-1900

In later years the ethnographic collection grew as a result of fieldwork and included the acquisition of important groups of material from Yemen and Palestine.

Palestinian bridal headdress, 1840s

Palestinian bridal headdress, 1840s

A more recent donation of over 400 20th-century objects from the Arabian Peninsula came from Leila Ingrams (1940–2015), collected as a result of her parents’ activities and travels in the Hadramaut and Zanzibar.

Carved wooden sandals or slippers, Zanzibar, 1930s

Carved wooden sandals or slippers, Zanzibar, 1930s

The collection continues to grow, thanks to donations such as those by the governments of Oman, Tajikistan and Uzbekistan.

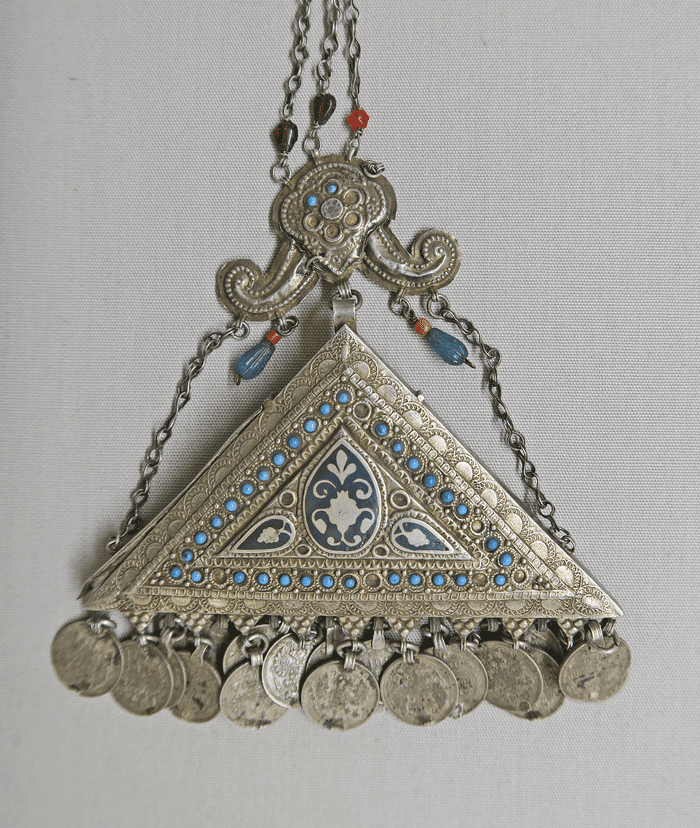

Amulet case, Tajikistan, 1900s

Amulet case, Tajikistan, 1900s

Another important part of the collection comprises the arts of the book. The relocation of the British Library, originally part of the Museum, to its current home at St Pancras in 1997, resulted in manuscripts and books being housed at St Pancras, while albums and single-page works remained in the Museum. These include masterpieces by celebrated artists and calligraphers such as Riza Abbasi (d. 1635).

Single-page painting of seated scribe, Iran, around 1600

Single-page painting of seated scribe, Iran, around 1600

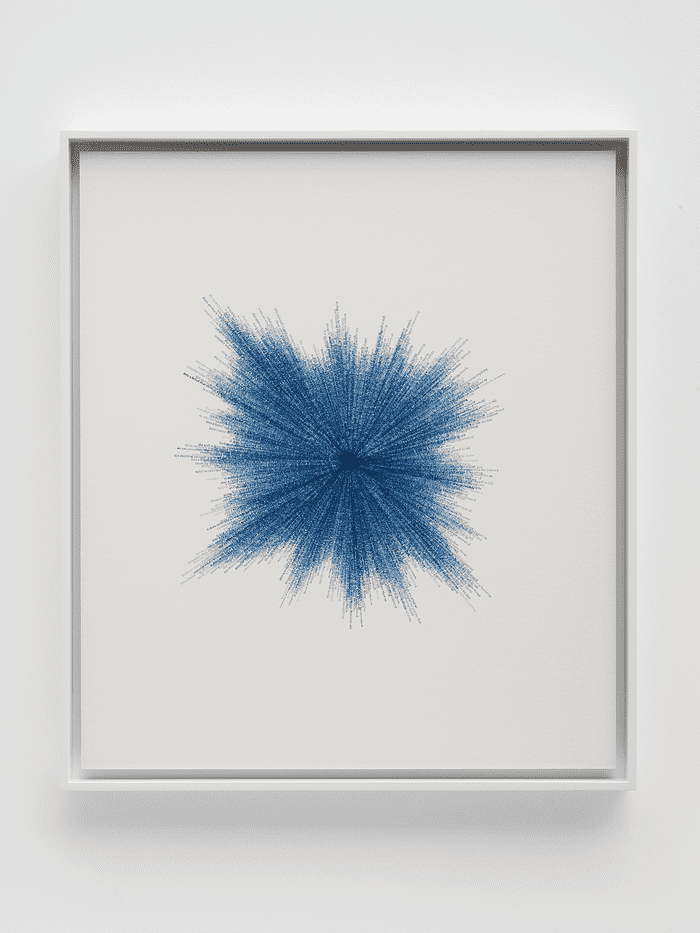

A new departure for the Museum has been the development of a collection of works on paper by modern artists. Including drawings and artists’ books, these often reflect the interaction of artists with their heritage, while offering complementary narratives to the complex histories of these regions today. The most recent acquisition, is a set of stamped paintings entitled ’21 stones’ commissioned for the new gallery by the British artist Idris Khan.

One of a series of 21 hand-stamped works on paper, 21 Stones, Idris Khan, 2018

One of a series of 21 hand-stamped works on paper, 21 Stones, Idris Khan, 2018

The new Albukhary Foundation gallery contains elements of all these remarkable collections of objects which have been brought together over time. Seen together, they present a remarkable testament to the richness and breadth of the cultures of the Islamic world. Some of the individual stories are highlighted in the Object Histories case, uncovering the journeys that brought these objects to the British Museum.