Lyre

BackDescription:

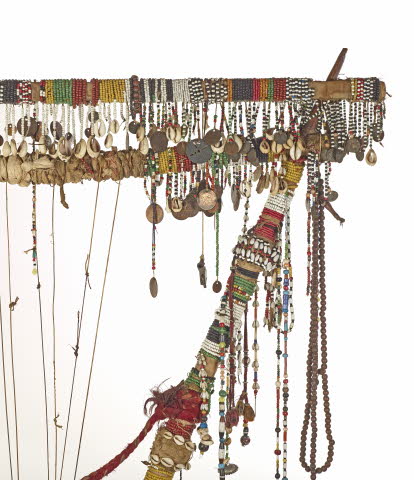

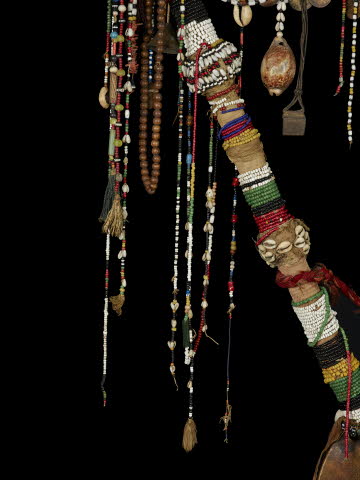

Large musical instrument, lyre, with two 'arms' set into a semi-spherical resonator of wood covered with skin, into which two circular apertures have been cut, giving the appearance of a face. Seven strings are attached to the resonator and are wound around the first of two cross pieces, both of which are covered with an assortment of pendant charms, coins and beads.

Object type: | lyre |

Museum number: | Af1917,0411.1 |

Date: | 19thC (late) |

Production place: | Made in: Sudan |

Findspot: | Found/Acquired: Sudan~Found/Acquired: Nile, River (Upper)~Found/Acquired: Uganda (?) |

Materials: | wood, skin, glass, cowrie shell, metal, gut, iron |

Technique: | beadwork, carved |

Dimensions: | Height: 121.50 cm Width: 116.00 cm Depth: 40.50 cm |

Location: | 41 |

Exhibition history: | Exhibited: 1995/6 Oct-Jan, Royal Academy of Arts, Africa: The Art of a Continent 1996 Mar-May, Berlin, Martin Gropius Bau, Africa: The Art of a Continent 1996 May-Sep, New York, Guggenheim Museum, Africa: The Art of a Continent 2001 Sainsbury African Galleries, British Museum 2015 Room 3 British Museum |

Acquisition names: | Donated by: Thomas Southgate |

Acquisition date: | 1917 |

Curator's comments:

This instrument, 'kissar', (also known as tanbura outside of northern Sudan) was owned by a musician who plied his trade in the nineteenth century at weddings and other important occasions. These probably included zār tanbura ceremonies – large, open-air events associated with sects across Sudan, Ethiopia and Egypt. Although the musicians at zār tanbura ceremonies are typically male, the primary audience is female. During these ceremonies, the lyre is played to calm restless spirits that have possessed the listener and to restore her to full health. The lyre is anthropomorphic, with two ‘eyes’, a ‘nose’ and outstretched ‘arms’ – and when played it has a ‘voice’. These instruments are perceived to have a spirit of their own and are the jealously guarded property of their owners. The name 'kissar' derives from the Nubian word ko:s (bowl) and can also refer to the cavity of the skull and thus to the bulbous resonator of the instrument. The 'kissar' is the leading instrument in a small band, which often include drums and tambourines. It is accompanied by a range of celebration songs collectively known as belal (beloved), that denote the various stages of marriage ceremonies. It would also have been played at other important life-cycle ceremonies, at harvest festivals and zār tanbura ceremonies. During the zār ceremony, women become entranced by the mesmeric rhythms of the musicians. They seek to communicate with and to placate whatever zār spirits have taken possession of their bodies in order to regain an equilibrium, which has somehow been disturbed. Zār ceremonies enable women to behave in ways, and to address issues, which would not normally be allowed in society. It is one of several vehicles for the communication of taboo subjects used in the wider region, such as written and symbolic messages on printed cloth such as 'kanga'. This lyre was created in the mid to late 1800s but the actual form of the instrument dates back thousands of years. The earliest known lyres (2600 BC) were excavated in the Royal Cemetery of Ur (modern Iraq). Examples and depictions occur in Assyrian wall reliefs from Nineveh in northern Iraq and tomb paintings in Ancient Egypt. More recent ancestors of the Sudanese lyre come from lands to the south in what is now northern Uganda and Kenya, where smaller but similar instruments are played today. The diverse objects attached to the lyre reflect Sudan’s central position and the movements of people, objects and faiths across the continent. It is festooned with glass beads, shells, bells, charms, coins and wooden prayer beads. The Ottoman coins attached to the lyre were minted in Cairo and Istanbul between 1860 (AH 1277) and 1876 (AH 1293). Sudan had been under Turco-Egyptian control since the 1820s, and Egypt itself was technically part of the Islamic Ottoman Empire. Under Turco-Egyptian rule, the centuries old trade in enslaved Africans had been centralised in Khartoum and by the late nineteenth century the city had become the largest slave market in the world. The musician who played this lyre was himself likely to have been enslaved, or at least came from a family of enslaved people. Zār spirits predominantly take a human form and may be inspired by people from many different parts of the world and from a wide range of professions and religious beliefs, including Catholic priests, Ethiopian Christian men as well as Egyptian, Yemeni and Turkish traders and officials. The objects attached to the lyre may have been placed there by the musician to appeal to individual spirits, or they may be offerings made by devotees of the zār cult. A Victorian halfpenny has been hung from the lyre, perhaps to appeal to zār spirits of European military and colonial officials. In the late nineteenth century the British intervened in Sudan, ostensibly to end the slave trade and to defeat the forces of the Khalifa, who led an army of followers on a jihad to reclaim Sudan from Turco-Egyptian control. In reality Britain’s military intervention waslargely motivated by a desire to pre-empt a French takeover of the upper Nile and to protect the Suez Canal and British interests in Egypt. Beads were one of the many forms of exchange used in Africa before the advent of minted and printed currency. In the early nineteenth century they were mass produced first in Venice, then in factories in England and France, for trading purposes in Africa. In the colour symbolism of zār, different colours appeal to different spirits. Green and white beads might represent Muslim spirits, red suggests Ethiopian Christian and possibly Catholic spirits, while black represents ‘pagans’ and potentially malevolent spirits. Today, the kissar continues to be played at weddings and large zār tanbura ceremonies in the region, while electric and amplified lyres reach a wider audience overseas through bands such as the Cairo-based RANGO collective.