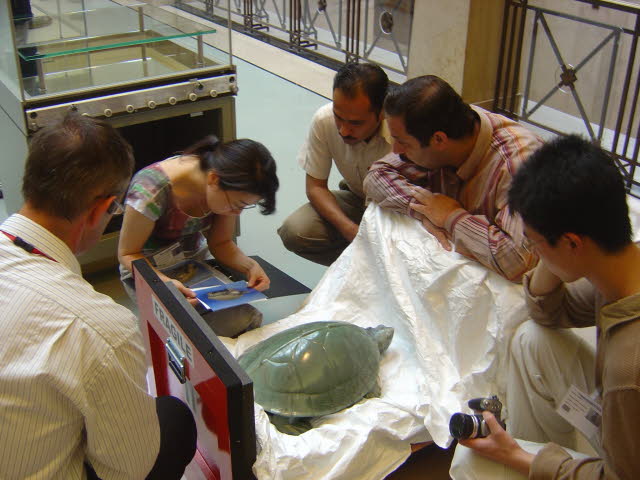

Figure

BackDescription:

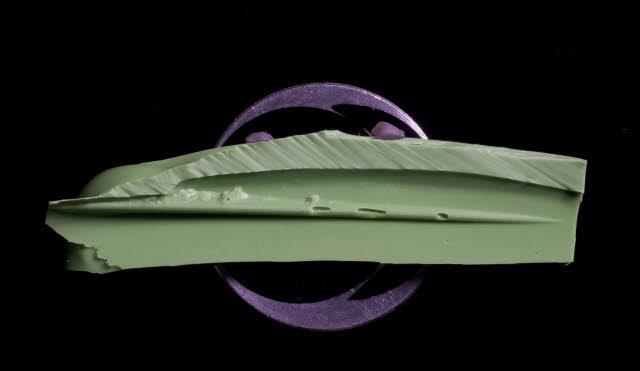

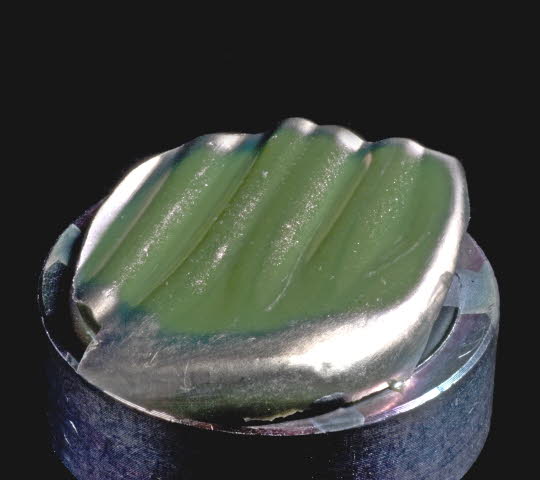

Life-size figure of an Indian terrapin (Kachuga dhongaka); carved from a single block of green nephrite, polished surfaces.

Object type: | figure |

Museum number: | 1830,0612.1 |

Culture/period: | Mughal dynasty |

Date: | 1600 (circa) |

Production place: | Made in: India |

Findspot: | Found/Acquired: Allahabad, a cistern in or near the Fort at Allahabad |

Materials: | nephrite |

Technique: | carved, polished |

Dimensions: | Weight: 41.00 kg Length: 48.50 cm Width: 32.00 cm Height: 20.00 cm |

Location: | 39 |

Exhibition history: | Exhibited: 2012-2013 8 Nov-10 Mar, London, British Library, 'Great Mughals: Myth, Reality and Legacy' 2006 UK Partner Tour, 'The Emperor's Terrapin' 1985-1986 14 Sept-5 Jan, New York, Metropolitan Museum of Art, 'India!', cat. 121 |

Subjects: | reptile |

Acquisition names: | Donated through: James Nairne, Esq~From: Thomas Wilkinson |

Acquisition date: | 1830 |

Curator's comments:

This stone carving of a terrapin was found during engineering work in 1803 at the Mughal fort at Allahabad, northern India. Previously the sacred Hindu city of Prag, Allahabad was fortified and so renamed by Akbar (r. 1556–1605), who then built a palace there as well. The Fort was occupied by his son, Prince Shah Selim, later the emperor Jahangir (r. 1605–1627). Jahangir, a patron of jade carving and a keen naturalist, may have commissioned the piece to decorate his palace gardens within the fort. The detailed carving work allows the species to be identified, i.e., a female 'Kachuga dhongoka' and native to the River Jumna which joins the Ganges at Allahabad. Spectroscopy testing confirms the stone to be nephrite, one of two main varieties of true jade. The size and appearance suggests the raw material originated from an unusual source, namely Xinjiang, then an independent central Asian kingdom. During a hazardous journey, the raw jade would have been carried around the Taklamakan Desert to Kashgar and then over the Karakorum Mountains to Kashmir and northern India. Nephrite is harder than iron so cannot be worked using metal tools. Electron microscopy indicates that the carving was worked with diamond abrasives and the fine shaping achieved with diamond-pointed tools. Diamond is the hardest mineral known; its use in gem work in India has a history going back to the first millennium BC. Using such hand-held tools this carving would probably have taken at least a year to create. Together with information about the source of the jade, and the quality of workmanship, this suggests a highly prestigious commission.; Presented to the Museum together with an inlaid marble table upon which the terrapin stood.